TECH TALK

Guest Post: Joe Skoczelak of JS & Sons Interior Finishes, LLC

Our TECH TALK post this week is from Joseph Skoczelak of JS & Sons Interior Finishes, LLC. Joe and his team provide quality drywall installation with integrity and innovation in Maryland.

In my 31-year drywall career, the debate over which method is best for fastening drywall to wood framing has never been put to rest. Because wood shrinks, twists, and bows, the best method and materials to use has been a tough nut to crack.

Lumber in general has decreased in quality. Because of the building boom and the need for lumber, most framing materials are cut from young growth – trees that are grown at rapid pace to keep up with the demand. Look at the ends of your average 2×4 and notice the spacing in the rings: the fewer the rings and the farther the spacing is in between them, the more volatile the drying out will be. As a result, the average 2×4 will shrink down to 3 1/4″ when fully dry. That is a full 1/8″ on both sides! Because of this shrinkage, blaming nails and screws for “popping” and “drying out” in the drywall is like blaming your skin for the bone breaking through in a compound fracture. In fact, the tighter the drywall is fastened to the stud, the greater the force when the drying process begins. Old-school thinking was to use a ton of glue because the installers must not be doing something properly. If that were the case the “pop” would show up almost immediately. Most of the fastener problems show up months after the installation is complete. This shows that it is more a matter of the wood drying out than improper installation.

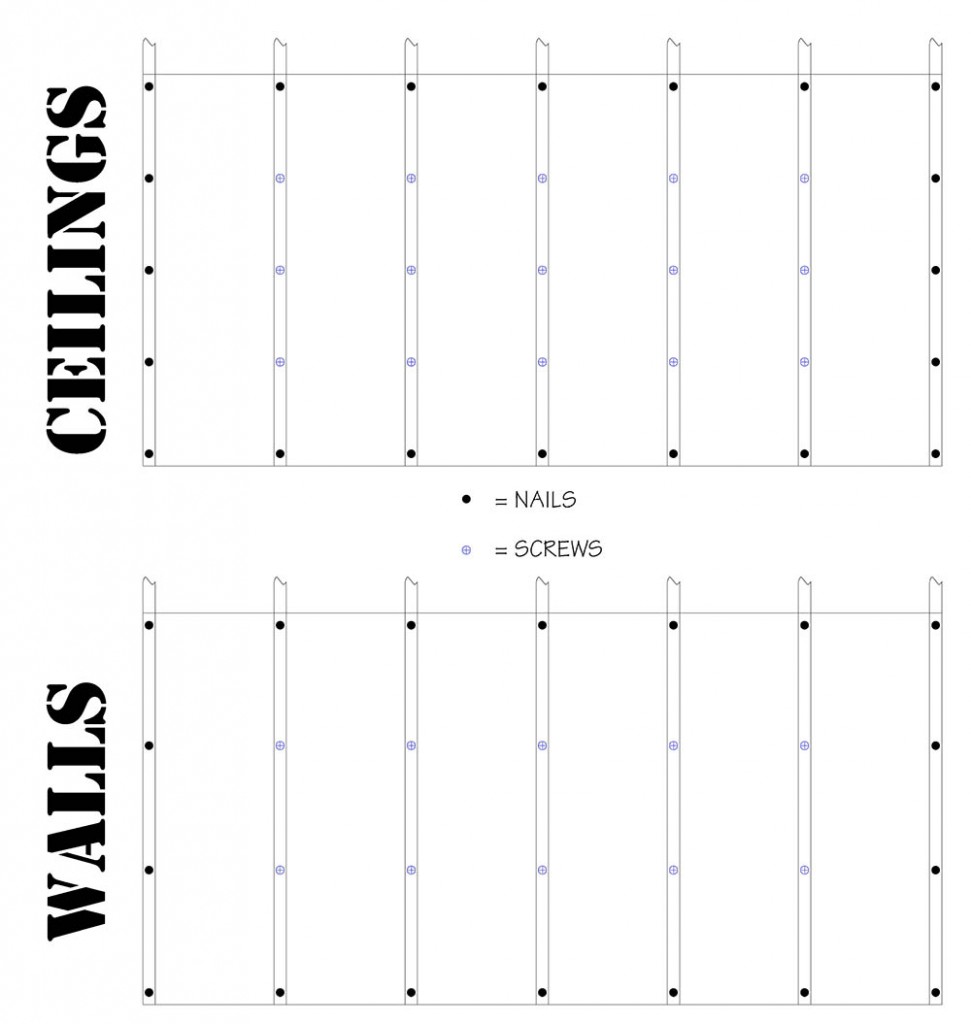

I have found the most effective method of eliminating these problems is to eliminate using glue and replace it with an additional screw in the field of the board. I prefer to nail the perimeters knowing that the fractured paper on the drywall is reinforced with the compound and tape on the edges. We use three screws in each framing member on the ceiling and two on the walls. This provides ample holding power and yet allows the drywall surface to absorb some of the movement of the wood’s drying process.

This still does not solve the problem of installing drywall on wood that has been rained on or otherwise has too high of a moisture content. Nor does it solve the problem in the winter of installing drywall in freezing temperatures, which causes the wood to expand only to shrink back down after the fasteners have been set at their proper depth. In general, though, we have had far fewer problems with fasteners since switching from gluing to implementing our additional fasteners method. Our builders were very skeptical at first. A few brave souls were frustrated enough with the drying-out phase that they allowed us to conduct our experiment on a few of their homes. The results were undeniable. Not a single builder has asked us to switch back to the old method.

Bigger homes, longer engineered spans, more lighting (natural and artificial) are all challenges to the cosmetic look of drywall which is not a plaster equivalent. While cosmetic expectations grow, the obstacles to delivering a quality product that will last are growing even faster. I believe new methods are worth trying to offset these very common problems.